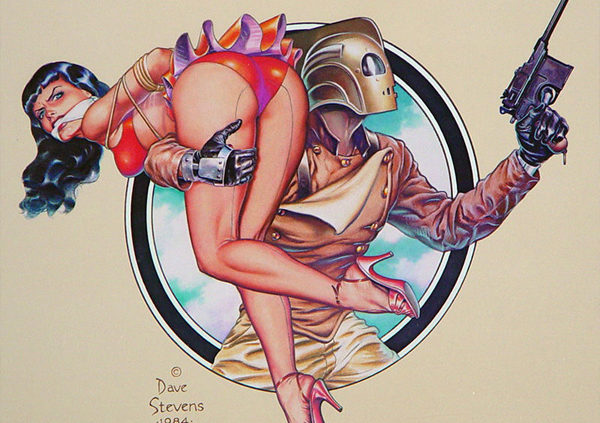

Bettie Page and THE ROCKETEER

Made in 1991, THE ROCKETEER is a film inspired by and really dedicated to Bettie Page. It is an old-fashioned adventure, full of innocent thrills and fun, about a youth with a high-flying dream.

Growing up in the Los Angeles suburb of Bell during the 1960s, Dave Stevens enjoyed watching silent cartoons on TV, and then chapter-play cliffhanger reissues at his neighborhood movie theater. They captured his imagination.

“What I wanted to do was draw,” Stevens remembered, “that’s all I thought about. And the things that inspired my illustrations were action-adventures from the old movie serials. I think I saw every one ever made. I was especially taken with such Republic Pictures cliffhangers as THE ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL (1941), KING OF THE ROCKET MEN (1949), and ZOMBIES OF THE STRATOSPHERE (1952). In some of these, the hero wore a rocket on his back in order to fly. As a kid I always wanted to fly like that.”

After high school, Stevens was employed to assist Russ Manning who drew the Sunday newspapers’ TARZAN comic strip. During this period Stevens happened upon a photo of underground pop culture icon Bettie Page, standing ankle-deep in the ocean, dressed in a bikini. “It stopped me cold,” the aspiring artist said of the sexy shot. “It took my breath away.”

Stevens had discovered a new obsession. He sought to learn all he could about the naughty-and-nice pinup queen known to some as “the Tennessee Tease,” and to others as “the Dark Angel.” Either way, Bettie Page was the original sweet-smiling bad girl next door.

Later, working as an animator for Hanna-Barbera in 1981, Stevens was asked by a comic press to contribute some “filler pages” for a new book. Still, always and ever-fascinated by Page, the soft-spoken illustrator sketched several concepts revolving around the cult model, but no scenario really jelled until Stevens combined her beautiful and dangerous persona with his own nostalgia for movie serials, and in particular with his boyhood fantasy of flying through the pre-war skies, just the way his airborne hero Captain Marvel did.

Stevens then at last had hit upon the winning concept for a new comic book hero from a bygone and more innocent era. The key was matching a perilous but playfully seductive Bettie Page type, as counterpoint girlfriend to a square-jawed, All-American, high-flying crime-fighter, propelled by a rocket on his back – “The Rocketeer.”

Comic book readers, pulp hero aficionados, and pinup fans alike all rushed to embrace the work. As though with divine authority, THE VILLAGE VOICE spoke for many when it hailed the new publication as an instant classic, “the greatest comic book in the world,” the paper enthused. A 1985 hardcover collection, offering five action chapters of THE ROCKETEER, featured an introduction by noted writer Harlan Ellison. “For all the hopeful attempts at doing a period comic book,” Ellison stated, “only THE ROCKETEER captures the feel of those days. The artwork is modern, yet it has a tone of the 1920s and 1930s.”

So it was Dave Stevens who first re-introduced Bettie Page in a big way to a new generation of eager fans. (Erotic pinup artist Olivia De Berardinis started painting Page in 1976, with ultimately more far-reaching, and amazing results.) And yet Stevens had never met his model, and could not find her. No one could. No one did.

Three decades earlier, the edgy pinup queen disappeared following the Estes Kefauver hearings with respect to pornography, as conducted in the United States Senate. Through the 1980s, no one knew what had become of Bettie Page. No one knew where she was, or even if she were still alive. Nevertheless, and without her knowledge, much less her consent, underground adulation and a cottage industry merchandising phenomenon followed. In a quiet way, in niche markets, Bettiemania ruled. For those who understood who Bettie Page was, no explanation for any of this was necessary. For those who did not know, probably no explanation was, or is, possible. No matter. The Page Craze was on.

Meanwhile, propelled by interest in Bettie Page, THE ROCKETEER soared, and executives at Walt Disney Pictures took notice. Filmmakers there saw the property as an adventure yarn that might challenge the boxoffice success of such other comic book movie adaptations as BATMAN in 1989, and DICK TRACY in 1990. Ultimately Stevens authored eight comic books, or graphic novels, as devotees termed them, all set in 1938. Disney paid a low six-figures sum for the screen rights.

Joe Johnston was signed to direct. He had just scored big – as in large — with his initial feature film HONEY, I SHRUNK THE KIDS (1989). A former production designer and whiz kid at Industrial Light & Magic, Johnston shared an Oscar for his dazzling special visual effects on RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981). He knew well how to capture the look, and the wonderful innocence of those old, action-packed Saturday matinee serials.

A budget was approved for $25 million. So THE ROCKETEER then constituted quite an expensive project for Disney at the time. In fact, much to the displeasure of those inside the Mouse House, the picture would eventually run another $10 million over budget.

To insure their ballooning investment, Disney went after Tom Cruise to star as the gee-whiz 1930s pilot. He declined. Johnny Depp was another name under consideration. But the studio settled on 6’4” Bill Campbell, a TV actor, and evidently heir to the Champion Spark Plugs fortune. “He’s Jimmy Stewart, age 25,” enthused director Johnston of their choice to play the cocky, straight-arrow racing pilot. Campbell was clean-cut, had a great smile, and a face unclouded by thought – exactly what the filmmakers wanted, or thought they wanted, except he was an unknown. Using non-stars has always been a calculated risk in Hollywood,, and was a long shot that ultimately did not pay off in this instance. Unfortunately, Campbell displayed little charisma before the cameras.

The whereabouts of bad-girl-next-door Bettie Page remained unknown. So the studio could not clear her name for use on-screen, nor in any of the film’s exploitation or character merchandising tie-ins. Plus the still squeaky-clean Disney studio was uneasy portraying a female lead suggested by a nude model with a dark and dangerous side. Trouble was, that component had been the key ingredient in the graphic novel’s success.

“The strip needed an edge,” Stevens explained, “a character people would remember. I thought the logical thing would be to put a bad girl in there next to this sweet guy.”

A week before filming was to begin, however, the script was altered. The Bettie Page part was rewritten, and her name changed to “Jenny Blake.” The name “Bettie Page” was never mentioned in any of the promotion. Only insiders who had devoured the comic books knew that THE ROCKETEER’S on-camera, cleaned-up leading lady was supposed to be, or should have been, the provocative pinup queen who had once rocked America, Bettie Page. Still professing purity, the Disney brand and Page’s guilty-pleasures-persona did not, could not, and would not mix.

First choice for the part was wholesome but bland Penelope Ann Miller, announced in the Hollywood trade papers August 11, 1990. Instead, however, and wisely, the role was awarded to winsome, stunning 19 year-old Jennifer Connelly. Previously, Sergio Leone used her for the small part of a young girl who dances in his gangster epic ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA (1984).

It turned out that Jennifer Connelly and Bettie Page had at least two things in common – heart-breaking good looks, and high intelligence. The gifted Connelly would study philosophy, quantum physics, and languages at Yale and Stanford. Meanwhile movie fans would study her amazing pneumatic figure in sensuous nude scenes filmed for THE HOT SPOT (1990).

The doe-eyed Connelly and wide-eyed Campbell made for quite a photogenic couple. They fell in love while making THE ROCKETEER, and were “engaged” for five years. In 2001 the curiously less voluptuous Connelly co-starred with Russell Crowe in A BEAUTIFUL MIND, for which she won an Oscar.

Strong British actor Timothy Dalton, a one-time James Bond, was signed to play a dashing, Errol Flynn-like Hollywood character, based on controversial biographer Charles Higham’s suspicious allegation that Flynn somehow had fascist leanings and once served as a Nazi agent — though who believed any part of that nonsense?

The sly villain Dalton portrayed was given the character name of Neville Sinclair. This moniker was derived from “Neville St. Clair,” out of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story THE MAN WITH THE TWISTED LIP.

The filmmakers even resorted to portraying a scene from THE ADVENTURES OF ROBIN HOOD (1938) to insure no one could miss that Dalton’s character (crooked as a barrel of snakes) was supposed to be the Warner Bros. star, Errol Flynn. And while there was a resemblance, Dalton has always suggested villainy in his roles – even as Bond – whereas Flynn never did.

Can you imagine how great this picture might have been in 1943, with the real Errol Flynn, not as the heavy, but rather as “The Rocketeer,” and the real Bettie Page, age 20, as his inamorata? In fact she did say on several occasions that failing to answer a telegram from studio boss Jack Warner about a screen test was the one mistake she most regretted in her life.

With the aid of makeup wizard Rick Baker, the brutish arch villain “Lothar” is clearly modeled after Rondo Hatton, an unfortunate character actor from the 1940s who had been deformed as the consequence of a condition called “acromegaly,” a pituitary disorder. Hatton was known to horror movie enthusiasts as “The Creeper.”

Stevens himself had a wish-fulfillment cameo as part of the Nazi test-flight movie footage. He can be glimpsed as the pilot with a rocket pack strapped to his back.

Like Stevens’comic book, the film is filled with inside pop culture references that must have been lost on targeted young moviegoers in 1991. Much less today. What teenagers would appreciate the impersonations of Clark Gable? Or W.C. Fields? Or understand the connection to Howard Hughes in the dirigible scenes reminiscent of his World War I aerial spectacle HELL’S ANGELS (1930)?

In Stevens’ comic book, 1930s pulp novel figure “Doc Savage” was the one who invented the rocket pack used for flying. When Disney balked at spending the money for clearance with the “Doc Savage” rights holder, Conde Nast, the studio substituted flamboyant aviator, and inventor, Howard Hughes, instead of Savage. At the time Disney owned The Spruce Goose, an enormous plane built by the quixotic Hughes. In 1990 it was then a money-losing attraction in need of promotion. So the studio referenced Hughes’ huge plane for some product placement advertising in THE ROCKETEER, even though there was as yet no Spruce Goose in 1938 when the film was set. Of course, who would know any part of that?

Moviegoers today may not be conversant with the once popular brand of gum known as “Beemans,” used in THE ROCKETEER. It was the alleged lucky chewing gum of pilots, which Hughes chose and chewed exclusively, don’t you know.

In real life, Howard Hughes pursued Bettie Page. As with many of the hottest starlets in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, Hughes phoned and had his staff phone Page many times, summoning her regularly on the pretext of wanting to photograph the delicious looking model. She declined every entreaty. “I never returned any of his calls,” said the celebrated pinup, who surprisingly few could pin down. “I guess people will say I made a mistake.”

So gifted in many ways, Page nevertheless did make her fair share of mistakes.

Having been delayed two months, principal photography on THE ROCKETEER finally commenced September 10, 1990. The 76 days-long shooting schedule proved to be optimistic. 96 days were required to finish the production, which concluded at last on January 22, 1991. Locations included the Santa Maria Airport, the Griffith Park Observatory, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis-Brown House in the Los Feliz district, and the Hollywood Sign, which Hugh Hefner twice paid to save and which once really did read “Hollywoodland,” as shown in the film, from 1923-1945.

With a PG rating and an array of art deco posters, Buena Vista Pictures Distribution issued the adventure fantasy to movie theaters on June 21, 1991. Some reviewers thought the effort was a tame period picture that never got off the ground. But VARIETY enthused, “This high-octane, high-flying, live-action comic strip has been machine-tooled into agreeable lightweight summer fare….Disney can chalk up one in the win column.”

Critic Kenneth Turan in the LOS ANGELES TIMES wisely lamented the loss of the daring and paradoxical Bettie Page persona in the transposition from script to screen. He also pointed out similarities with other updated cliffhangers such as RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (1981) and STAR WARS (1977), except, as he declared, that the less hip ROCKETEER does not kid the genre, and instead “plays things if not totally straight, more so than one would have thought possible, much less desirable.”

Roger Ebert in the CHICAGO SUN-TIMES leveled the same criticism, wishing for “the wit and self-mocking irony” of the Indiana Jones and STAR WARS series. These assessments may be dead-on insofar as gauging the film’s potential appeal for 1991 and even more contemporary audiences, but are completely irrelevant to me. That THE ROCKETEER is a faithful recreation of the Saturday Matinee experience is, to my mind, an enormous plus, not a minus. I much prefer the old-fashioned values offered during an age of innocence in movies, the one which ended when serials did, in the 1950s.

Disney hoped THE ROCKETEER would be the first of a franchise, and might even lead to a theme parks attraction. But in tests, it failed to excite today’s more cynical kids aged 14 and under. Boxoffice expectations flamed out accordingly, and crashed in a heap.

As mentioned, the picture cost at least $35 million. I should have asked the late Dave Stevens for all the figures, but never did. We know for sure only the domestic boxoffice gross, or ticket sales, amounted to $46,704,056. That meant domestic film rentals to Disney totaled $23,179,000. Or, not nearly enough. It meant likely commercial failure.

Meanwhile where was the inspiration for all of this? Had she seen THE ROCKETEER? Where was the real Bettie Page? Deceased? Hiding? Incapacitated? Guilty, in self-imposed exile? Who knew? No one did. Many searched. All efforts were unavailing.

After 1957 Bettie Page fled New York City for Florida, gave her life to Christianity, or at least tried to, married, divorced, and suffered a nervous breakdown. Her upbringing would explain probable cause. Throughout what she later called “my troubles,” Page hadn’t the least idea of the magic she left behind for so many others to discover and delight in, much less her impact on America’s fashion, sexuality, and pop culture.

Just about the time THE ROCKETEER finished unspooling, in its final play dates at neighborhood theaters around the country, coincidentally, Bettie Page was being conditionally released from behind the asylum walls of Patton State Hospital in Southern California. She had been diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic, and sent there for ten years, after the court accepted her plea of not guilty, by reason of insanity, to the charge of attempted murder, and assault with a deadly weapon, in 1982.

It was not until late in 1992 that Dave Stevens finally met Bettie Page. It was not until two years later that she finally saw THE ROCKETEER. In the December, 1995 issue, PLAYBOY reported (and so it has been frequently repeated in print ever since) that “she saw the film for the first time – and loved it – at a screening at the Playboy Mansion for her, Stevens, and a small group of friends.”

In fact, only four of us saw THE ROCKETEER that evening: Bettie Page, her trusted friend Dave Stevens, Hugh Hefner, and me. We met her together, for the first time, at the same time. She asked not to be photographed. She signed a still for me. And she answered every question we had for her, but in a low, soft-spoken monotone voice, and with a Southern drawl, all of which did not seem to match up with the playful personality one would guess at from her thousands of pinup photos.

A dozen years later, in 2006, Bettie Page recalled that screening. It may be a curse, that in fact she remembers everything she has done and seen in her long life, beginning with the first movie she ever saw. It happened to be James Whale’s classic thriller THE OLD DARK HOUSE (1932) – she slept with the lights on for weeks.

“I enjoyed seeing THE ROCKETEER that day at Hugh Hefner’s house, I really did,” Page said in 2006, “but I liked the house even better than the movie! I liked all the animals, and the secret panels, too. That’s a man who knows how to live!” Ironically, during the 1960s, Bettie Page had spent a year working as a counselor for the Billy Graham Crusades in Chicago, near the original Playboy Mansion.

Bill Campbell never did marry Jennifer Connelly and live happily ever after. Dave Stevens divorced the B-movies “scream queen” he married, and died of complications from leukemia earlier this year, at age 52. The last time I spoke with him was on the phone, at Bettie Page’s home, in January of 2007. He could barely speak above a whisper.

Bettie Mae Page, the Queen of Pinups, passed on December 11, 2008 at Kindred Hospital in Los Angeles. She has left lasting marks, inspired many, and influenced more.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!